UTAH OPERA, The Abduction from the Seraglio, Capitol Theatre, May 10; through May 18, tickets at 801-355-2787, 888-451-2787 or www.utahopera.org

If one had to choose one word to summarize Utah Opera’s current production of The Abduction from the Seraglio, it might be “inconsistent.” Why?

Let’s start with the highlights: the vocals were strong. Really strong. Andrew Stenson, in the leading male role of Belmonte, had a smooth, velvety voice that was a pleasure to listen to. Gustav Andreassen’s (Osmin’s) bass was rich, full, and beautiful without being muddy or heavy. Celena Shafer, in the lead soprano role of Konstanze, also gave an excellent vocal performance. The rest of the voices were also first rate, with no vocal weak links in the cast.

In terms of overall performances, Amy Owens (Blonde) and Tyson Miller (Pedrillo) were engaging, charismatic, and gave strong performances both with vocals and acting throughout the show. Andreasson presented a perfect bad guy: funny, engaging, with just the right amount of menace.

So why the adjective “inconsistent?” The problem with opera is that it’s not a recital; the people onstage are expected to act, as well. Therein lies the weak spot. We have high expectations of our opera singers, really — we want world-class pipes, and acting ability besides. It’s a tall order, but without both, the whole experience falls a bit flat.

Perhaps the biggest problem with this production of The Abduction from the Seraglio is that the weak links were so prominent.

Shafer had a voice that was very much up to the demanding role: clear and agile, she handled the acrobatics of the music beautifully. She could float a high C at a pianissimo. But her acting did not keep pace with her voice. Throughout the production, she came across either as stiff and stilted or over-dramatic, but never natural. Her facial emotion and body language sometimes seemed at odds with the words she was singing.

Christopher McBeth in the spoken role of Pasha Selim, appeared to have little acting experience on stage. Doubtless McBeth excels in his role as Artistic Director for Utah Opera, but as to delivering his lines in a convincing manner that could project well (either in terms of emotion or volume), he fell a bit short of the mark.

Thankfully, Owens added a much-needed dose of energy and spunk to the production. A natural on the stage, she stole the show with the scene in Act II when she teases Osmin and stands up to him. Andreasson and Miller both added a lot of vigor and humor with their characterizations.

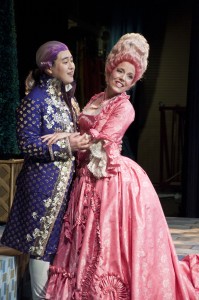

As to the costumes, the bare chest and rather conspicuous codpiece of Pasha Selim’s costume seemed intended to emphasize his sexual prowess — and perhaps it did, in a way. And Konstanze’s eye-popping pink dress and matching hair were very…pink. While the costumes generally enhanced the production, these two detracted a little because they were a bit distracting.

To sum it up: if you are a person who loves to hear great singing, the more the better, this production might be a heavenly way to spend the evening. But if you are a newcomer to opera, this probably isn’t the best introduction. This is not one of Mozart’s most famous or popular operas. And while the overall effect was fine, this production may not make any new converts.