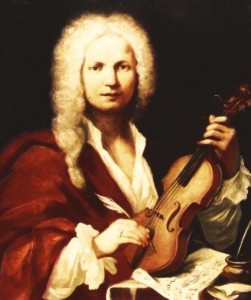

1713 marked a major changing of the guard in the music world. It was the year that 60-year-old Arcangelo Corelli died in Rome and an up-and-coming Venetian, Antonio Vivaldi, composed La Stravaganza. On this 300th anniversary of those events, I’ve programed three masterpieces by each of the two geniuses for the 2013 Vivaldi by Candlelight concert.

Corelli, rich and revered when he died, was recognized as the foremost violinist and composer in Europe. He had brought the concerto grosso, by far the most popular form of instrumental ensemble composition, to its pinnacle. Vivaldi was getting warmed up with his Opus 3, L’estro armonico, a set of 12 concertos for one, two and four violin soloists and strings. Published in Amsterdam in 1711, Vivaldi began to be noticed internationally. With his Opus 4, La Stravaganza, a set of 12 mind-bending concertos for one violin soloist and strings, which he composed in 1713 and had published a year later, Vivaldi charted new territory for the concerto form, harmonic invention and the potential of the violin as a solo instrument.

Ravel and Debussy. Mahler and Bruckner. Mozart and Haydn. How many times have you heard the music of one composer and guessed it was the other? Corelli and Vivaldi. It will never happen. Why not? Let me count the ways.

First off Corelli never composed a solo concerto and Vivaldi never composed a concerto grosso. (Music historians may quibble over that statement, depending on how broadly they define concerto grosso, but as mathematicians might say, such deviations would be statistically insignificant.)

What is a concerto grosso? It is a multi-movement composition for an ensemble essentially comprising an orchestra within an orchestra, one of solo (or concertato) players interacting with the larger tutti (or ripieno) group. The potential of permutations between instruments in this multi-movement form is almost infinite – concertato with ripieno as accompaniment; concertato and ripieno in dialogue, or all playing together; individual concertato players; contrapuntal treatments in which instruments imitate each other’s melodic lines; vertical monophonic statements of chords played in unison; etc. Corelli takes advantage of them all in such a creative and masterful way that it masks an unexcelled level of expertise and good taste. Keep your eyes and ears open as you watch the kaleidoscope of interaction during the performance. One goes away humming thoroughly engaging melodies that connect to the listener at a very deep level. At the same time, we have open-mouthed admiration of his unparalleled craftsmanship.

After Corelli, the concerto grosso continued for another generation or two before the upstart symphony, thanks to Haydn and Mozart, claimed the throne. Certainly Handel wrote his share of excellent concerti grossi, patterned after Corelli, and Bach had his Brandenburgs. But I dare to say – as with Beethoven in relation to Mozart – if not for Corelli, Bach’s and Handel’s achievements in the genre could never have happened. And though the Brandenburgs might be more complex and instrumentally innovative, the beauty of Corelli’s concerti grossi are unsurpassed.

Vivaldi almost single-handedly invented the three-movement concerto, and the fast-slow-fast succession of movements he championed has remained the standard template for concertos ever since. The soloist (or soloists) in his concertos dominates the landscape. Overt virtuosity is integral to the overall conception. Back in the day, it was not uncommon for composers to write concertos that were not necessarily intended to be performed by a particular instrument, but rather could be played by a variety of instruments in a given register: violin or flute or oboe, for example. No doubt, sales were one consideration for such generic writing, but the bigger issue was the role of the soloist in the broader context of “the concert.” Since a lot of music was composed for purposes of light entertainment and background music, it was not so important who played on what instrument, as long as the music was pleasant and unobtrusive.

The concertos of La Stravaganza, on the other hand, are so instrumentally idiomatic they can be played only on the violin. I’d hazard a guess that the term “in your face” didn’t exist in 18th century Venice; nevertheless, that’s the impression these concertos make upon the listener. No background music here. Unlike the harmonically conservative Corelli, Vivaldi delights in exploring exotic key relationships and dissonant harmonies. Rhythm becomes a structural component and driving force of his fast movements, not unlike Beethoven in the 19th century and Stravinsky in the 20th. The critical development in these concertos, though, is that the soloist wrests the spotlight from the ensemble. It is the beginning of the esthetic of the soloist as hero, dominating the landscape, struggling against orchestral forces and emerging triumphant; a theme developed by literally hundreds of later composers, including Beethoven, Brahms and Tchaikovsky.

Music historians have regrettably divided the history of Western tonal music into four arbitrary “periods” which are identified by meaningless and counterproductive names: Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and something called Modern, which actually means Everything Since. (I wonder how many centuries Modern can continue to be called Modern.) These designations have been the stated case for so long that we assume there everything within a given period was similar, and everything between periods was different, so we lose crucial connections like those between Bach and Brahms, or Handel and Beethoven. Yet there was as much change within the Baroque period, which the history books tell us lasted from about 1600 to 1750 (Monteverdi through the death of Bach) as within Modern (from Debussy through the present). Considering the significance of 1713, the year the torch was passed from the concerto grosso to the solo concerto, a year in which the world began to bid farewell to music still under the gravitational force of the Renaissance, and said hello to an esthetic that still reverberates in music composed today, I would be tempted to make the claim that “pre-Vivaldi” or “post-Corelli” makes for a much more informative historical designation. At least it would pay due respect to two great masters.

You can hear everything I’m talking about by attending the 2013 Vivaldi by Candlelight concert on Saturday, December 7, at 8:00 p.m. at the First Presbyterian Church, South Temple at C Street, Salt Lake City. It’s the 31st annual benefit for the Utah Council of Citizen Diplomacy (UCCD) and my 10th anniversary as Music Director.

For more information log on to http://utahdiplomacy.org/what-we-do/vivaldi-by-candlelight-a-benefit-concert/.

Pingback: SATURDAY’S VIVALDI BY CANDLELIGHT MARKS GERALD ELIAS’ 10TH ANNIVERSARY AS MUSIC DIRECTOR | Reichel Recommends